Investigating the Relative Age Effect at Yale

I just finished reading Malcolm Gladwell’s best-seller, Outliers. Naturally, I was curious about some of his claims and decided to do a little investigating of my own.

Gladwell starts the book by suggesting the existence of the following “iron law” of Canadian hockey: “in any elite group of hockey players — the very best of the best — 40 percent of the players will have been born between January and March, 30 percent between April and June, 20 percent between July and September, and 10 percent between October and December.”

Why would this be the case? It turns out that Canadian hockey leagues impose an eligibility cut-off date of January 1, meaning that a child born in January competes in the same league as a child born in December, almost an entire year later. These extra months of maturity, according to a study conducted by psychologist Roger Barnsley, give an unfair advantage to kids born earlier in the year — by virtue of being older, these kids tend to be larger, more coordinated, and more “talented” than their peers. Those that are deemed more talented go on to enjoy the rewards of better coaching, increased self-confidence, and more opportunities, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that is driven entirely by an arbitrary cut-off.

This phenomenon is known as the relative age effect. And both Gladwell and Barnsley suggest that it occurs within academia and education as well. Like hockey leagues, schools have an eligibility cut-off date (usually, the end of summer) and often separate students based on relative merit (gifted student programs). To further this argument, Gladwell points to the research of economists Kelly Bedard and Elizabeth Dhuey, who have noted that “at four year colleges in the United States… students belonging to the relatively youngest group in their class are underrepresented by about 11.6 percent.”

With this knowledge in hand, I decided to poke around and see if I could find any interesting patterns at Yale, hoping to answer the following question: does the relative age effect impact your chances of making it to Yale?

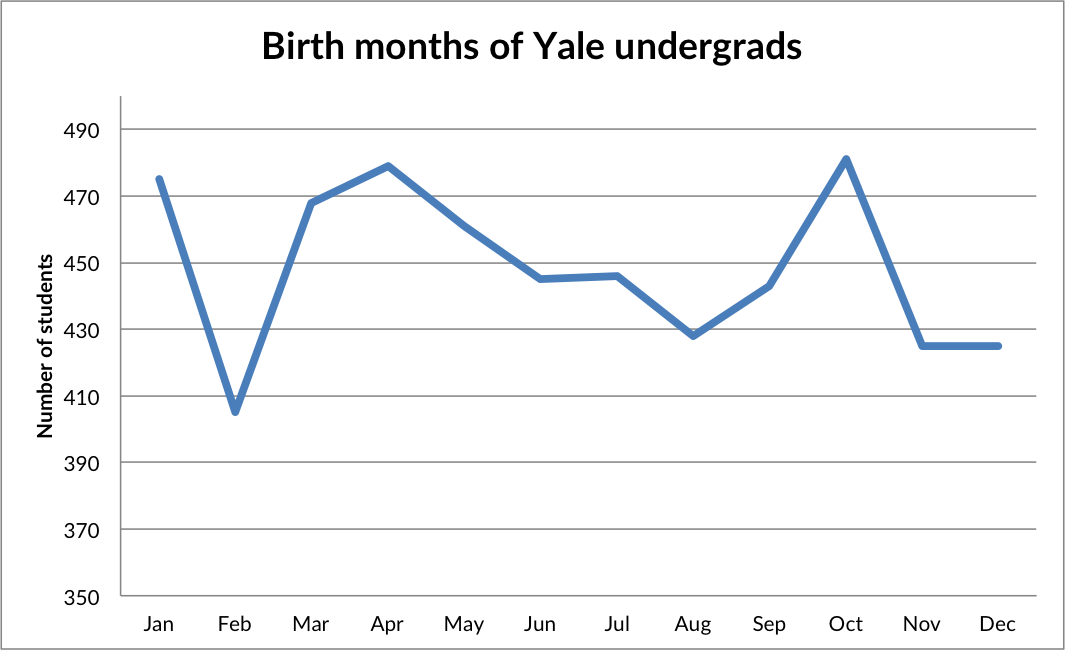

Since I’m currently an undergrad at Yale, I have access to the walled-off Yale Facebook, a directory that contains basic biographical and contact information for all current undergraduate students. Here’s the scraped and compiled data, which includes the class of 2015 up to the class of 2019 (5565 students total, 5381 of which have their birthdays listed):

- January: 475

- February: 405

- March: 468

- April: 479

- May: 461

- June: 445

- July: 446

- August: 428

- September: 443

- October: 481

- November: 425

- December: 425

It seems that the relative age effect doesn’t apply: Yale undergrads are born evenly throughout the year, with a range of 76, a mean of around 448, and a fairly low standard deviation of around 25. And the most unpopular birth month is February, which also happens to be the shortest month of the year. If we adjust for the 10 or so lost days of February between the classes of 2015 and 2019, the data would show even less variance than it does now.

However, it can’t hurt to point out that the graph has three local maximums, two of which might be relevant to the relative age effect: one around October (close to the start of school in the Northern hemisphere), one in March and April (close to the start of school in the Southern hemisphere) and one in January (which I don’t have a relavant explanation for).

It’s also worth noting that according to data compiled by Amitabh Chandra of Harvard University, the second half of September is the most common time of year for U.S.-born babies (approximately 81% of the Yale population hold U.S. citizenship or permanent resident status), providing an alternate explanation for that particular local maximum.

There are, unfortunately, some limitations to what we can do with this data. The Yale Facebook does not list birth years, which makes it impossible to filter out students who may have entered school a year early, or who may have skipped a grade or two. However, if we assume that these kids do exist in the pool, we might be able to say that the relative age effect did not play a role in their development — that is, for the truly precocious, relative age differences do not play a major role in their educational development. This isn’t a certain conclusion, however, since the other side of the coin in not having birth years is that we also are unable to filter out students who may have purposely “redshirted” before starting kindergarten or who may have taken a gap year in between high school and college, thus making them older than their peers by the time they enter college.

But empirically, at least, it appears that most early age biases at Yale have been erased or never existed in the first place. 1

Could it be that Yale admissions officers are familiar with the relative age effect and consciously adjust for this in their admissions process? This is possible, but probably unlikely.

Here’s another possibility: as mentioned earlier, 19% of Yale students are listed as international students. What if, out of this 19%, almost every student that attended school in the Southern hemisphere was born in the months of March and April, balancing out a presumably lower amount of students in the Northern hemisphere that were also born in those months? If true, this could have created the local maximum that we see in March and April. And while relying purely on geography is an imperfect filter for determining when school starts, it should at least give us a working estimate to play with.

When I went to test this hypothesis, I quickly discovered that this was not the case. Of the 83 students with addresses in the Southern hemisphere (Argentina, Australia, Botswana, Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Kenya, Mauritius, New Zealand, Peru, Rwanda, Singapore, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe), only 14 were born in March and April. The most common birth months were actually June and July.

The best explanation I’ve seen thus far comes from Maria Konnikova from The New Yorker. In her “Youngest Kid, Smartest Kid?” essay, Konnikova suggests that while older kindergarten students do benefit from their age, “by the time they get to eighth grade, any disparity has largely evened out — and, by college, younger students repeatedly outperform older ones in any given year.” Older students, she argues, become bored and complacent, while younger students embrace their underdog statuses and are forced to strive and push themselves harder, developing a work ethic that even Gladwell can appreciate.

Thanks to Jonathan Chang for reading a draft of this essay.

-

Note: this experiment only tests for the relative age bias. I am positive that there are many other biases and barriers in this data set that can not be explained solely by age. ↩